I wrote this piece in 2022 when Liz Truss was Prime Minister. I am reposting it now in light of the recent piece by David Aikman, Director of NIESR who is advocating for tax increases in the UK in the Autumn budget. If the government follows that advice, and if marginal rates are increased on high earners, there is likely to be a further exodus of high net worth individuals and a possible drop in revenue to the UK Treasury. I present some evidence from the Osbourne tax experiment from 2010 to 2012 to support my argument.

Charlottesville VA, October 2022.

The change of leadership in the United Kingdom has generated a fair bit of comment in the UK press and in the international community more generally. Of all the policy changes that the Truss government has announced, the one that has generated the most opprobrium from the domestic and international commentariat is the proposal to reduce the marginal tax rate on incomes higher than £150,000 from 45% to 40%. I realize that this is not a popular opinion: but there is a case to be made that this particular tweak may well be revenue enhancing.

First, let me remind you of the liberal/establishment consensus. Here is the Sunday Times in their October 2nd, 2022, leader

“… the prime minister and chancellor have made economic conditions more challenging and snookered themselves politically. Undoing even part of their £45 billion in tax cuts — particularly the eye-catching scrapping of the 45p top income tax rate – could fatally damage Truss in the eyes of her MPs …. Giving a £2 billion windfall to 600,000 top-rate taxpayers while shrinking benefits for the most vulnerable looks awful.” [Sunday Times, October 2nd, 2022, my emphasis]

It's not just the UK establishment that is unsettled by the Truss-Kwarteng proposal to cut the top marginal tax rate. In a remarkable intervention in domestic politics that goes well beyond their remit, the International Monetary Fund issued the following comment:

“We are closely monitoring recent economic developments in the UK … the nature of the UK measures will likely increase inequality. The November 23 budget will present an early opportunity for the UK government to consider ways to provide support that is more targeted and re-evaluate the tax measures, especially those that benefit high income earners.” [IMF Statement on the UK (September 27, 2022), my emphasis][1]

In my opinion, restoring the top tax rate on earned income from 45% to 40%, – the rate that applied under the two previous Labour Chancellors – will not result in economic Armageddon although there is certainly a case to be made that it is politically unwise.

During the period from 1999 to 2009, the top marginal tax rate was 40%, the same rate that Kwarteng is proposing to reintroduce in the September ‘not-a-budget’.[2] For three years from 2010 to 2012, the top marginal rate was raised by George Osborne to 50% for those earning more than £150,000. In 2013 it dropped back to 45% for those in the top tax bracket where it remained until this month. So, what was the effect on UK tax revenues?

Roughly 25% of UK tax revenue, 10% of GDP, is raised by taxes on labour income. These taxes can be broken down into two groups. Basic-rate and high-rate. In 2018, basic-rate taxpayers were those earning less than a threshold – about £42,000 in 2018 – and high-rate taxpayers were those earning more than the threshold. In 2018 there were 26 million basic-rate taxpayers, each of whom paid 20% of their income in taxes and 4 million high-rate taxpayers, each of whom paid 40% on every pound they earned above the £42,000 threshold.

In 2011, George Osborne split high-rate taxpayers into two groups. Those earning below £150,000 continued to pay a top rate of 40%. Those earning above £150,000, of whom there were less than 300,000 people in 2010, paid 50% on income above £150,000. The result of these changes in marginal tax-rates provides an experiment that we can learn from today.

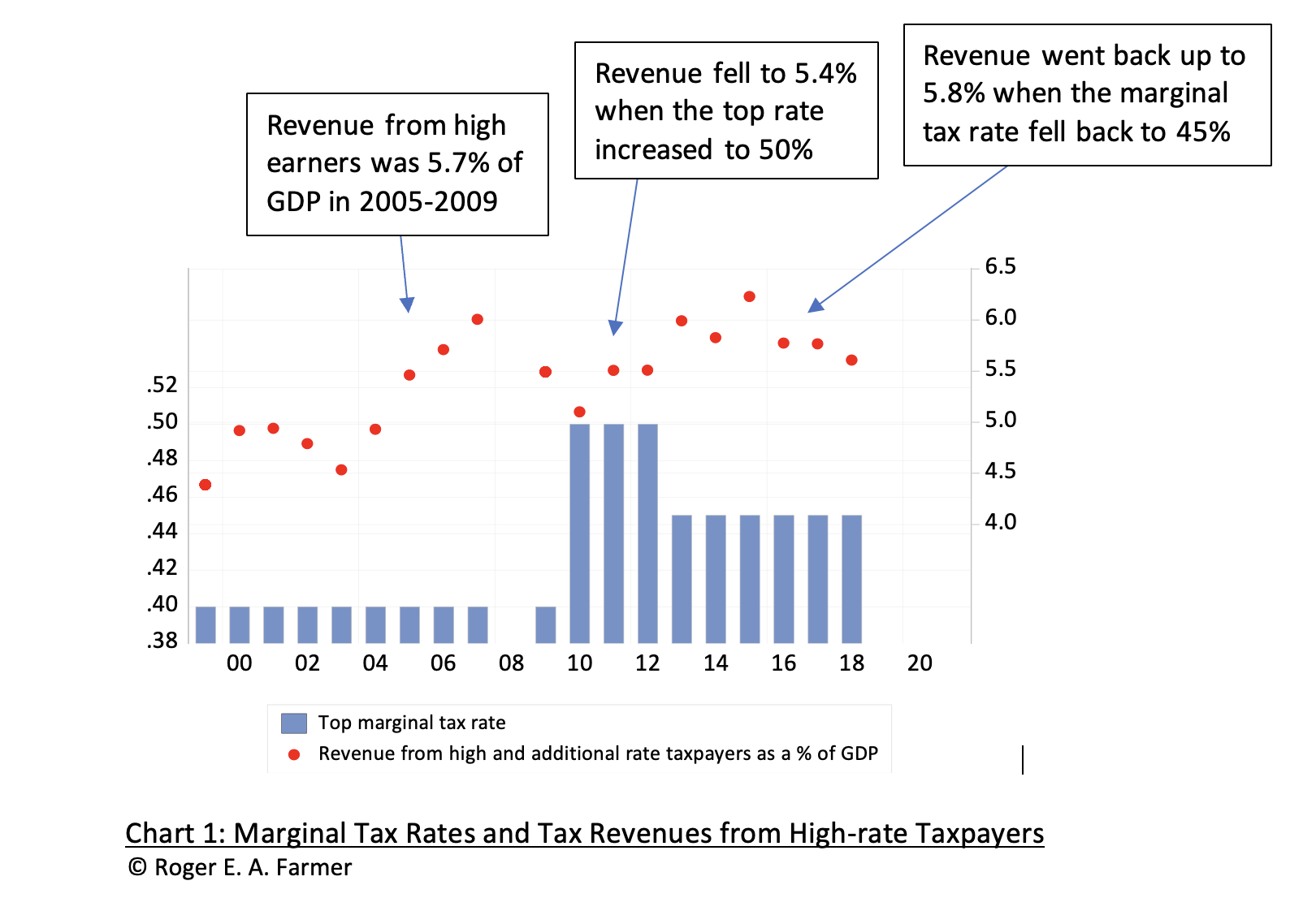

Chart 1 shows the impact of the Osborne tax experiment on the UK Treasury. The vertical bars measure the top marginal tax rate. The red dots measure revenue raised from high-end taxpayers (everyone above the £42,000 threshold) as a percentage of GDP. Although there are ten times more basic-rate taxpayers than high-rate taxpayers, the revenue raised from high-rate taxpayers – £121 billion in 2018 – is twice as much as the revenue raised from basic-rate taxpayers which was £61 billion in 2018.

Revenue from high earners in the five years from 2005-2009, before the Osborne experiment, was on average equal to 5.7% of GDP. In the three years from 2010 to 2012, when the top tax rate was 50%, revenues from high-rate taxpayers fell to 5.4% and when the tax rate fell back to 45% in 2013, revenues picked up again to 5.8%, roughly the same as in the earlier period.

The Osbourne experiment of raising the marginal tax rate from 40% to 50% suggests that a marginal tax rate of 50% is too high and that lowering the rate back to 45% was revenue enhancing. The UK under Osborne was on the wrong side of the Laffer curve. Will a further cut from 45% to 40% raise or lower revenue? The Osborne experiment suggests that the effect may be a wash and that the peak of the Laffer curve (the marginal tax rate that maximizes revenue) is somewhere in the range of 40% to 45%.

Is the proposed Truss-Kwarteng cut in the top tax-rate to 40% politically wise? Probably not, given the current state of UK politics. Will it lower revenue by £2 billion as claimed in the Sunday Times Leader? Almost certainly not and that particular aspect of the not-a-budget may even be revenue enhancing.

Roger E. A. Farmer.

Professor of Economics, University of Warwick.

Distinguished Emeritus Professor of Economics, UCLA

[1] https://www.imf.org/en/Countries/GBR Retrieved October 2nd 2022

[12 The following analysis draws mainly on data published by the Office of National Statistics, Table 2.5a, which presents data on tax rates and tax revenues by income. These data begin in 1999, when Gordon Brown was Chancellor of the Exchequer under the Blair government and run through the 2018-2019 tax year when Philip Hammond was Chancellor under Teresa May.