I have lost count of the number of times I have heard students and faculty repeat the idea in seminars, that “all models are wrong”. This aphorism, attributed to George Box, is the battle cry of the Minnesota calibrator, a breed of macroeconomist, inspired by Ed Prescott, one of the most important and influential economists of the last century.

All models are wrong... all models are wrong...

Of course all models are wrong. That is trivially true: it is the definition of a model. But the cry has been used for three decades to poke fun at attempts to use serious econometric methods to analyze time series data. Time series methods were inconvenient to the nascent Real Business Cycle Program that Ed pioneered because the models that he favored were, and still are, overwhelmingly rejected by the facts. That is inconvenient.

Ed’s response was pure genius. If the model and the data are in conflict, the data must be wrong. Time series econometrics, according to Ed, was crushing the acorn before it had time to grow into a tree. His response was not only to reformulate the theory, but also to reformulate the way in which that theory was to be judged. In a puff of calibrator’s smoke, the history of time series econometrics was relegated to the dustbin of history to take its place alongside alchemy, the ether, and the theory of phlogiston.

How did Ed achieve this remarkable feat of prestidigitation? First, he argued that we should focus on a small subset of the properties of the data. Since the work of Ragnar Frisch, economists have recognized that economic time series can be modeled as linear difference equations, hit by random shocks. These time series move together in different ways at different frequencies.

For example, consumption, investment and GDP are all growing over time. The low frequency movement in these series is called the trend. Ed argued that the trends in time series are a nuisance if we are interested in understanding business cycles and he proposed to remove them with a filter. Roughly speaking, he plotted a smooth curve through each individual series and subtracted the wiggles from the trend. Importantly, Ed’s approach removes a different trend from each series and the trends are discarded when evaluating the success of the theory.

After removing trends, Ed was left with the wiggles. He proposed that we should evaluate our economic theories of business cycles by how well they explain co-movements among the wiggles. When his theory failed to clear the 8ft hurdle of the Olympic high jump, he lowered the bar to 5ft and persuaded us all that leaping over this high school bar was a success.

Keynesians protested. But they did not protest loudly enough and ultimately it became common, even among serious econometricians, to filter their data with the eponymous Hodrick Prescott filter.

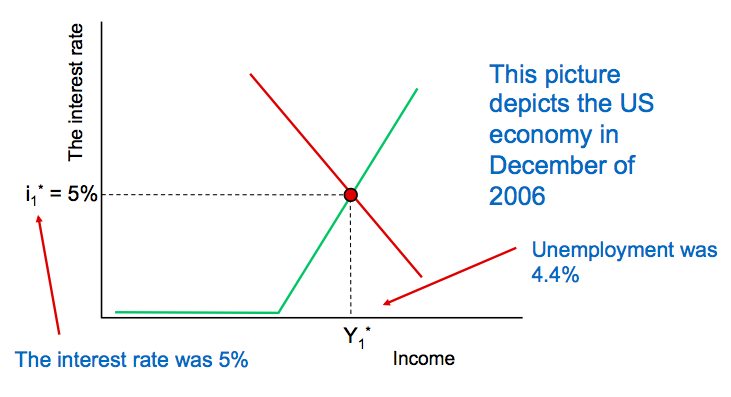

Ed’s argument was that business cycles are all about the co-movements that occur among employment, GDP, consumption and investment at frequencies of 4 to 8 years. These movements describe deviations of a market economy from its natural rate of unemployment that, according to Ed, are caused by the substitution of labor effort of households between times of plenty and times of famine. A recession, according to this theory, is what Modigliani famously referred to as a ‘sudden attack of contagious laziness’.

The Keynesians disagreed. They argued that whatever causes a recession, low employment persists because of ‘frictions’ that prevent wages and prices from adjusting to their correct levels. The Keynesian view was guided by Samuelson’s neoclassical synthesis which accepted the idea that business cycles are fluctuations around a unique classical steady state.

By accepting the neo-classical synthesis, Keynesian economists had agreed to play by real business cycle rules. They both accepted that the economy is a self-stabilizing system that, left to itself, would gravitate back to the unique natural rate of unemployment. And for this reason, the Keynesians agreed to play by Ed’s rules. They filtered the data and set the bar at the high school level.

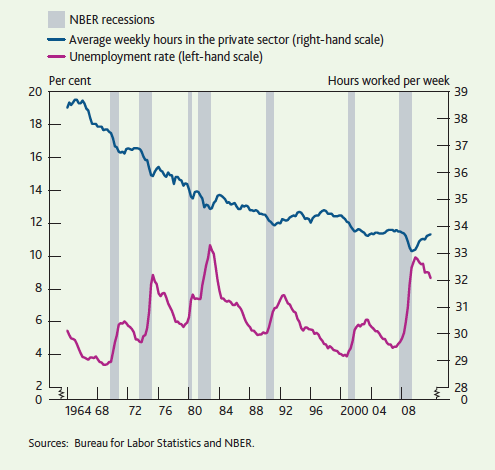

Keynesian economics is not about the wiggles. It is about permanent long-run shifts in the equilibrium unemployment rate caused by changes in the animal spirits of participants in the asset markets. By filtering the data, we remove the possibility of evaluating a model which predicts that shifts in aggregate demand cause permanent shifts in unemployment. We have given up the game before it starts by allowing the other side to shift the goal posts.

We don't have to play by Ed's rules. We can use the methods developed by Rob Engle and Clive Granger as Giovanni Nicolò and I have done here. Once we allow aggregate demand to influence permanently the unemployment rate, the data do not look kindly on either real business cycle models or on the new-Keynesian approach. It's time to get serious about macroeconomic science and put back the Olympic bar.