In the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries the business cycle was a wild ride. Part of the damage inflicted by financial crises was caused by price instability. That problem was successfully solved in the 1980s when the Fed adopted inflation targeting. The success proved chimeric. My last post argued for a second policy, designed to stabilize the stock market. This policy, in combination with an inflation targeting rule, would effectively dampen financial cycles.

My previous post provoked a number of responses on Twitter that I will respond to here. Sanjay Mittai, @sanjmitt asked;

"What about stabilizing employment? Or are workers to be regarded as trash as long as the stock market is doing OK?"

My proposal to stabilize the stock market is based on two research papers, here, and here, in which I show that there has been a strong and stable connection between the stock market and the unemployment rate in six decades of US data. Stock market crashes, when they are sustained for six months or more, lead to recessions. Persistent bull markets lead to unsustainably low unemployment rates and the creation of unsustainably high levels of capital creation. The euphoria always eventually comes to a painful end for the average worker when the market crashes and he or she is out of a job.

The proposal, explained in my book Prosperity for All, is to stabilize the asset markets with the ultimate goal of maintaining full employment. Part of my argument is aimed at my fellow economists. I explain why financial markets do not work well, even when everyone alive today can trade assets contingent on every conceivable future event. And part of my argument is aimed at my fellow citizens. I seek support to create an institution that is not aimed to improve the lives of the rich and powerful: it is aimed to improve the lives of all of us.

A second point was raised by John the Blind, @Athena_Alithis who is concerned that low volatility is the calm before a future storm. Here is John;

By stabilising the stock market, the system becomes more unstable and risky. Less vol means higher leverage and larger risk portfolios building up as ‘what could possibly be wrong.’

To which I respond: The world we live in today is not the same world that our Mothers and Fathers inhabited. It is not the world that our Grandmothers and our Grandfathers inhabited. It has evolved in ways that none of us, even ten years ago, could have foreseen. The institutions that we built to tame financial cycles have been, at least partially, successful. That success is evidenced by a fall in the frequency of financial panics which occurred far more often in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

We achieved increased stability by creating new institutions like the Federal Reserve System which learned successfully to manage price stability for more than three decades from 1980 through 2007, a period we now call the ‘Great Moderation’. That stability was not an illusion. It was a creation of improved monetary management. It ended in 2008 because the tool we had used to manage markets, control of the short rate of interest, hit zero and could be lowered no further.

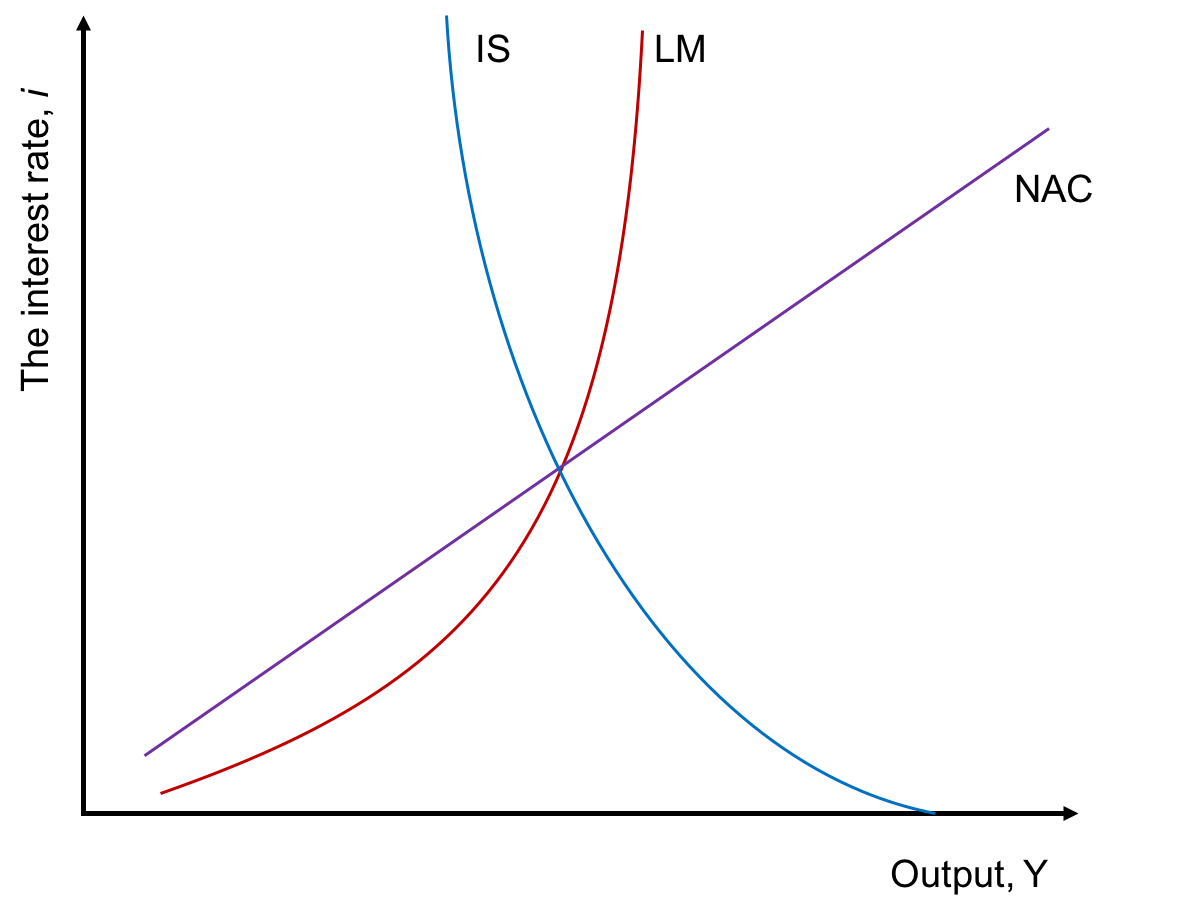

The Great Recession was a large natural experiment that we can, and should, learn from. The lesson is not that we must tear up existing institutions and go back to the Gold Standard. It is that we must develop new institutions. By managing the short rate of interest we tamed the lion of inflation. By managing the risk composition of the average market portfolio we can tame the lion of unemployment and help to bring Prosperity for All.